Arizona is one of the fastest-growing states in the U.S., with an economy that offers many opportunities for workers and businesses. But it faces a daunting challenge: a water crisis that could seriously constrain its economic growth and vitality.

A recent report that projected a roughly 4% shortfall in groundwater supplies in the Phoenix area over the next 100 years prompted the state to curtail new approval of groundwater-dependent residential development in some of the region’s fast-growing suburbs. Moreover, negotiations continue over dwindling supplies from the Colorado River, which historically supplied more than a third of the state’s water.

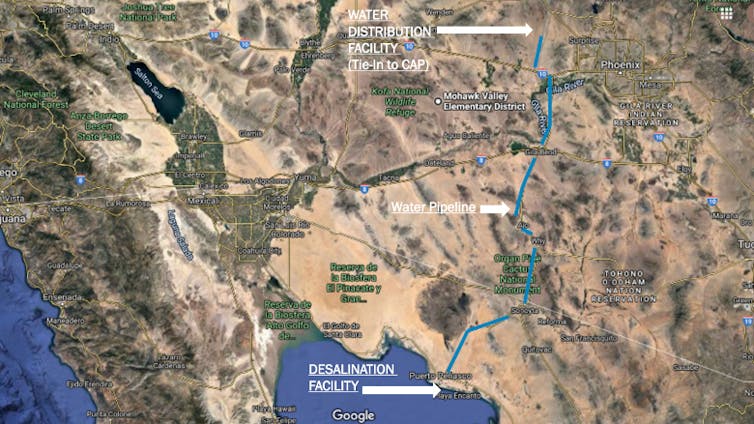

As a partial solution, the Arizona Water Infrastructure Finance Authority is exploring a proposal to import desalinated water from Mexico. Conceptualized by IDE, an Israeli company with extensive experience in the desalination sector, this mega-engineering project calls for building a plant in Mexico and piping the water about 200 miles and uphill more than 2,000 feet to Arizona.

Ultimately, the project is slated to cost more than US$5 billion and provide fresh water at nearly 10 times the cost of water Arizona currently draws from the Colorado River, not including long-term energy and maintenance costs.

Is this a wise investment? It is hard to say, since details are still forthcoming. It is also unclear how the proposal fits with Arizona’s plans for investing in its water supplies – because, unlike some states, Arizona has no state water plan.

As researchers who focus on water law, policy and management, we recommend engineered projects like this one be considered as part of a broader water management portfolio that responds holistically to imbalances in supply and demand. And such decisions should address known and potential consequences and costs down the road. Israel’s approach to desalination offers insights that Arizona would do well to consider.

Lands and waters at risk

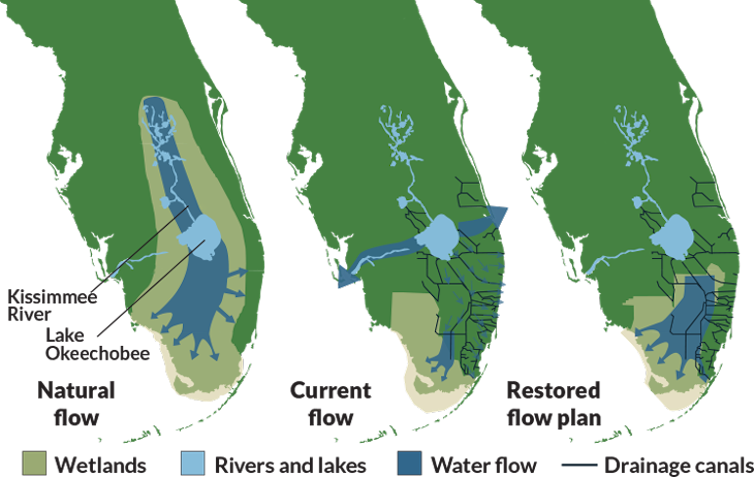

Around the world, water engineering projects have caused large-scale ecological damage that governments now are spending heavily to repair. Draining and straightening the Florida Everglades in the 1950s and ′60s, which seriously harmed water quality and wildlife, is one well-known example.

Israel’s Hula wetlands is another. In the 1950s, Israeli water managers viewed the wetlands north of the Sea of Galilee as a malaria-infested swamp that, if drained, would eradicate mosquitoes and open up the area for farming. The project was an unmitigated failure that led to dust storms, land degradation and the loss of many unique animals and plants.

Arizona is in crisis now due to a combination of water management gaps and climatic changes. Groundwater withdrawals, which in much of rural Arizona remain unregulated, include unchecked pumping by foreign agricultural interests that ship their crops overseas. Moreover, with the Colorado River now in its 23rd year of drought, Arizona is being forced to reduce its dependence on the river and seek new water sources.

The desalination plant that Arizona is considering would be built in Puerto Peñasco, a Mexican resort town on the northern edge of the Gulf of California, also known as the Sea of Cortez. Highly saline brine left over from the desalination process would be released into the gulf.

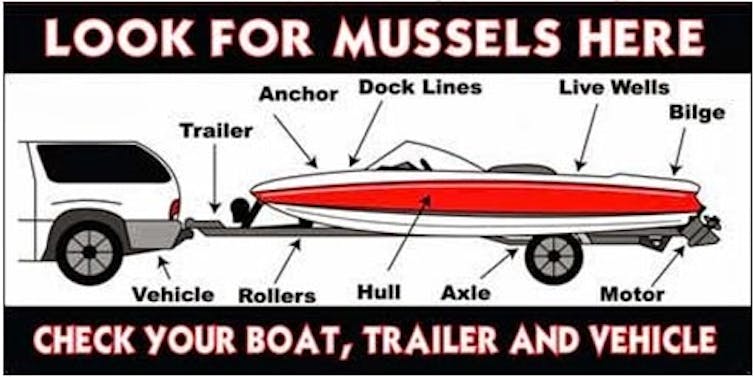

Because this inlet has an elongated, baylike geography, salt could concentrate in its upper region, harming endangered aquatic species such as the totoaba fish and the vaquita porpoise, the world’s most endangered marine mammal.

The pipeline that would carry desalinated water to Arizona would cross through Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, a fragile desert ecosystem and UNESCO biosphere reserve that has already been damaged by construction of the U.S.-Mexico border wall. To run the facility, IDE proposes to build a power plant in Arizona and lay transmission lines across the same fragile desert.

No single solution

Israel has adapted to water scarcity and has learned from its disastrous venture in the Hula wetlands. Today the country has a water sector master plan that is regularly updated and draws on water recycling and reuse, as well as a significant desalination program.

Israel also has implemented extensive water conservation, efficiency and recycling programs, as well as a broad economic review of desalination. Together, these sources now meet most of the nation’s water needs, and Israel has become a leader in both water technology and policy innovation.

Water rights and laws in Arizona differ from those of Israel, and Arizona isn’t as close to seawater. Nonetheless, in our view Israel’s approach is relevant as Arizona works to close its water demand-supply gap.

Steps Arizona can take now

In our view, Arizona would do well to follow Israel’s lead. A logical first step would be making conservation programs, which are required in some parts of Arizona, mandatory statewide.

Irrigated agriculture uses more than 70% of Arizona’s water supply, and most of the state’s irrigated lands use flood irrigation – pumping or bringing water into fields and letting it flow over the ground. Greater use of drip irrigation, which delivers water to plant roots through plastic pipes, and other water-saving techniques and technologies would reduce agricultural water use.

Arizona households, which sometimes use as much as 70% of residential water for lawns and landscaping, also have a conservation role to play. And the mining sector’s groundwater use presently is largely exempt from state regulations and withdrawal restrictions.

A proactive and holistic water management approach should apply to all sectors of the economy, including industry. Arizona also should continue to expand programs for agricultural, municipal and industrial wastewater reuse.

Desalination need not be off the table. But, as in Israel, we see it as part of a multifaceted and integrated series of solutions. By exploring the economic, technical and environmental feasibility of alternative solutions, Arizona could develop a water portfolio that would be far more likely than massive investments in seawater desalination to achieve the sustainable and secure water future that the state seeks.

Clive Lipchin is affiliated with the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies.

Gabriel Eckstein and Sharon B. Megdal do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.